The challenge of compelling fiction

My wife, Barbara, works from home, and because I'm out in the world, I procure library books for her to read. Mostly, she likes novels. She often reads late at night. A few days after she's started a new book, I'll ask her how it's going.

"It's killing me!" is a frequent response.

"Then don't read it!" I say, in a paroxysm of guilt. "I'll take it back! I'll get you a happier book!"

Usually, she rejects this offer and continues struggling with the book she already has. A few days later, when I ask again how she's doing with it, she often says, "It's wonderful! You should read it!"

And so it goes.

The quest for "a happier book"

What about this idea of "a happier book?" A few years ago, I took a course in writing short stories. In the anthology we used as our text, one author makes the blanket statement, "Stories are about problems."

He goes on to explain what many who write about writing have said: without a conflict, there’s no story.

In mythic time, or dreamtime, there’s always a kind of Garden representing Being—a perfect place beyond time and decay. Our world is the world of flux, of becoming. Here, we’re hopefully working out our salvation and our karma. The Garden is here, too, but it’s impossible to see. It's represented by the World-Tree, which seems to grow in this world but actually grows in, or to, another. Spiritual sages are often shown sitting at the foot of this tree.

We may feel perfection in Nature, in love, in art or in some uplifting event like the crumbling of the Berlin Wall. But this is likely to be a fleeting glance. We're told that an Age of Intuition is coming. There are even statistics, such as drops in the crime rate, which seem to bear this out. However, our world is still one of flux, of lessons, and some of the lessons are very hard.

A journey through the darkest of times

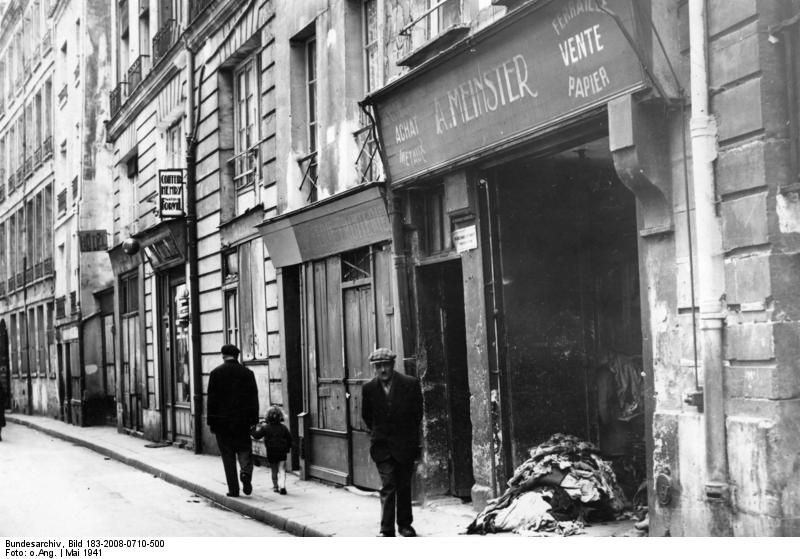

In The Nightingale, Kristen Hannah's magnificent novel that I recently read at Barbara's recommendation, the characters live in France during the Nazi occupation of the Second World War.

Only the first few pages of the book give readers a picture of the country before the war. The difficulties of the life that begins with the German invasion are repeatedly ratcheted up as the occupation progresses, until the book becomes almost unbearable to read. Only my concern for the characters I'd come to care about prevented me from putting it down.

How did those who survived the ordeal of German occupation manage to retain any integrity? The answer to that question is the mystery that kept me reading The Nightingale. The best of literature, in my opinion, reveals the resiliency of the human spirit. How can such resiliency even be known, unless it's tested?

I couldn't, for the life of me, imagine doing the things that the brave men and women of the French Resistance do in the novel. Their every act becomes a risking of life, as Jean-Paul Sartre remarked in a memoir about his own days in occupied France.

There is no romanticizing these lives. No one would want to trade places. I naturally resist even thinking about such cruelty, threats and heartbreaking loss. Novels such as The Nightingale force me to do so, however. They force me to consider what in life is worthy of sacrifice, what has real meaning and what ennobles human beings.

Perhaps we never know what bravery and honour we're capable of until we're tested under duress. The characters in The Nightingale certainly didn't. At first, some of them try to hide. But things grow steadily worse, as the Nazis perpetrate more and more indignities. They force the French to witness the deportation of Jews and others who've been their neighbours for generations. Self-respect demands that the characters we get to know accept the cup life has served them, and begin risking their lives to help the cause.

The starkest reality dramatized by Hannah is the clear truth that although some of the Germans are family men who've been drafted, or career soldiers who don't share Hitler's maniacal hatred, the Gestapo and the Schutzstaffel (SS) are made up of psychopathic sadists who don't even regard their victims as human. An SS officer billeted in the home of one of the main characters forces her to feed his men, cooking lavish dinners made from food only Germans are allowed to have. Then he throws the leftovers to the chickens in the backyard, rather than feeding his starving hostess and her children.

Fiction as therapy

Such inhumanity remains endemic in the world, of course. We live our privileged lives while people in the Middle East, Africa and even within our own borders continue to suffer at the hands of tormentors. How can we go on, knowing this? We must try to relieve suffering, and yet, avoid perishing from survivor's guilt.

Books like The Nightingale help dispel our complacency. The enduring values they reveal and champion must be defended and supported, whether by contributions to charities, political action, fervent prayer or other means. We aren't islands.

I'm thankful to Kristen Hannah for pinching me in my dream, enough to awaken me a little bit. I believe that gripping narrative fiction such as this book enables readers to place themselves imaginatively in situations that expand awareness of life's possibilities. I'm grateful to authors who write with such authority that their "fiction" comes alive, expands my universe and challenges me, too, to respond to life in braver and more committed ways.

«RELATED READ» HEARTFELT HISTORY: How novels put the individual at the centre of the same stories textbooks tell»

image 1: Pixabay, image 2: Das Bundesarchiv via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons BY-SA)

Click to Post