Rainer Dr. Werning

Frechen-Königsdorf

-

Noch keine BeiträgeHier wird noch geschrieben ... bitte schaue bald nochmal vorbei

Rainer Dr. Werning

-

ostasien

-

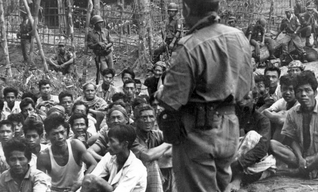

philippinen

-

zeitgeschichte

-

südostasien

-

entwicklungspolitik

-

interkulturelle kommunikation

-

nord-)korea

-

länderanalysen

Kurzinfo zur Person:

Dr. Rainer Werning ist Politikwissenschaftler und Publizist mit den Schwerpunkten Südost- und Ostasien. Seit 1970 u.a. mehrfache und längere Studienaufenthalte in den Philippinen; Autor zahlreicher Publikationen über die Regionen und ehemals Lehrbeauftragter an den Universitäten Bonn und Osnabrück. Er ist u.a. Mitglied im Wissenschaftlichen Beirat der Offenen Akademie sowie im Bereich Landesanalyse und Kultur als Philippinen- & (Nord-)Korea-Dozent an der Akademie für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (AIZ) in Bonn tätig.

Auftraggeber

"ORIENTIERUNGEN" - Zeitschrift zur Kultur Asiens , KOREA forum , Korea-Info , Lebenshaus Schwäbische Alb , Länderinformationsportal Philippinen , Publikationen , Sicht vom Hochblauen , WOZ , Zeit , Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek , ag-friedensforschung.de , akweb.de Indonesien , akweb.de Korea (Nord) , akweb.de Korea (Süd) , asienhaus.de , blaetter.de , brennpunkt.lu , bulatlat.com , bulatlat.com , doam.org , doam.org , doam.org , dp-freunde.de , elib.gov.ph , fisch-und-vogel.de , freitag.de , hintergrund.de , jungewelt.de , jungle.world , nachdenkseiten.de , nd-aktuell.de , nomos-elibrary.de , pacific-geographies.org , rf-news.de , südostasien , taz.de , wissenschaft-und-frieden.de , zeitpunkt.ch

Weitere Profile

Academia - Papers by Rainer Werning , Podcast von Rainer Werning

Fehler!

Leider konnte der Artikel nicht gefunden werden.

We can't find the internet

Attempting to reconnect

Something went wrong!

Hang in there while we get back on track