Alexander Stirn

München

-

Noch keine BeiträgeHier wird noch geschrieben ... bitte schaue bald nochmal vorbei

Alexander Stirn

-

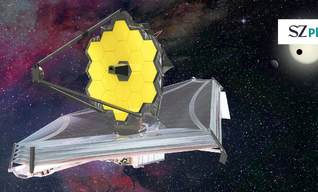

astronomie

-

fotografie

-

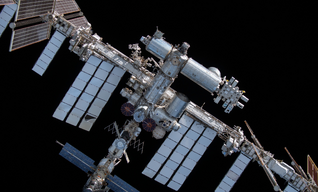

raumfahrt

-

technik

-

wissenschaft

-

reportagen

-

mobilität

-

luftfahrt

Werdegang

Alexander Stirn, Jahrgang 1972, lebt, schreibt und bloggt als freier Wissenschaftsjournalist in München. Wenn er nicht gerade Nasa-TV schaut, berichtet er über Luft- und Raumfahrt, Astronomie sowie über alles, was Drähte, Schrauben oder Schaltkreise hat.

Berufserfahrung: Redakteur und Chef vom Dienst beim Magazin “Süddeutsche Zeitung WISSEN”, Ressortleiter Wissenschaft bei “Spiegel Online”, Wissensredakteur bei “Matador”. Seit Juli 2007 freier Wissenschaftsjournalist mit eigenem Redaktionsbüro

Ausbildung: Deutsche Journalistenschule (DJS) in München, 40. Lehrredaktion (Kompaktklasse)

Studium: Physikstudium an der Universität Würzburg und der University of Texas in Austin, Studium der Politischen Wissenschaft, Soziologie und Volkswirtschaftslehre an der Universität Würzburg

Auszeichnungen

UMSICHT-Wissenschaftspreis – Kategorie Journalismus

2016: Preisträger für „Goldgrund“

Hugo-Junkers-Preis der Deutschen Luft- und Raumfahrtpresse

2012: Preisträger für „Sternwarte im Jumbojet“

PUNKT – acatech-Preis für Technikjournalismus

2012: 1. Preis „Tageszeitung“ für „Klempner am Meeresgrund“

Deutscher Journalistenpreis für Luft– und Raumfahrt

2011: 1. Preis (Print) für „All-Tours“

PUNKT – acatech-Preis für Technikjournalismus

2009: 1. Preis (Tageszeitung) für „Rochenflügel“

Ludwig-Bölkow-Journalistenpreis

2006: 1. Preis (Print) für „Fliegende Flunder“

Axel Springer Preis für Junge Journalisten

2002: 1. Preis (Online) für „15 Jahre Mir: Ende einer Dienstfahrt“

Stipendien

Robert-Bosch-Stiftung

2013: Medienbotschafter China-Deutschland

Auftraggeber

NZZ , National Geographic , P.M. Magazin , Spektrum der Wissenschaft , Süddeutsche Zeitung , Technology Review

Weitere Profile

Facebook , Flickr , Instagram , LinkedIn , Twitter

Fehler!

Leider konnte der Artikel nicht gefunden werden.

We can't find the internet

Attempting to reconnect

Something went wrong!

Hang in there while we get back on track