A man can't know where he is on the earth except in relation to the moon or a star. Astronomy comes first; land maps follow because of it. Just the opposite of what you'd expect. If you think about it long enough, it will turn your brain inside-out. A here exists only in relation to a there, not the other way around. There's this only because there's that; if we don't look up, we'll never know what's down. Think of it, boy. We find ourselves only by looking to what we're not. You can't put your feet on the ground until you've touched the sky.-Thomas Effing in Paul Auster's Moon Palace

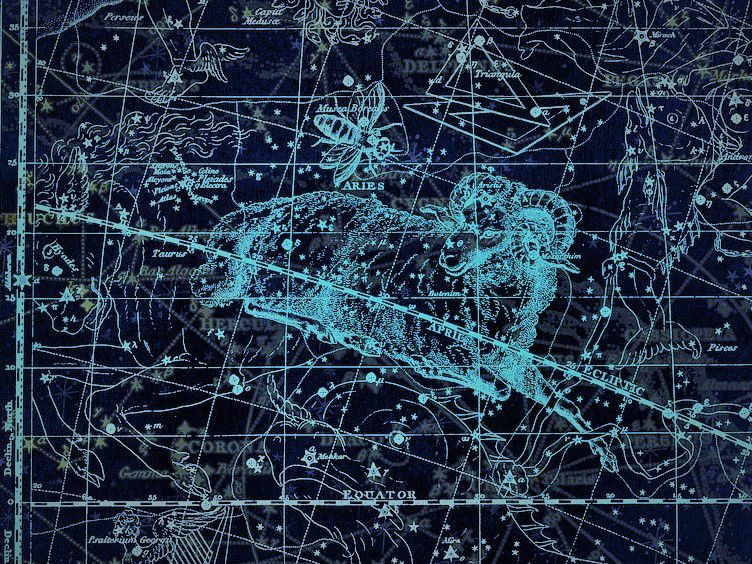

It is not hard to understand why the ancient Sumerians, when they looked at the firmament at night, were moved to discern patterns in the cluster of glowing lights. After all, humans are evolutionarily wired and trained to find sense and order in the chaos of everyday experience. The map of zodiac signs they drew up is still in use by astrologers today-and increasingly so in recent years, as almost anyone who has an Instagram account will surely have noticed. As traditional religion is understandably falling out of favour, many people-especially in the United States-are turning again to astrology to fulfil their spiritual needs.

Knowing the movement patterns of the orbs allowed early humanity to determine its place on earth, as the quotation from Moon Palace illustrates. Since they lacked the benefits of the Enlightenment revolution, which separated astronomy from astrology, the Sumerians may be forgiven for trying to find extra-terrestrial explanations for other earthly problems and for assuming that the arrangement of the blazing dots might tell them something about the next harvest or the evil intentions of a neighbour. They did not know that they were actually observing suns akin to the one that nourishes life on earth, just as they were unaware of so many things we have since learned: from the physical laws of the cosmos down to the existence of microbes.

Modern people, however, can put forward no such excuse. While the stars help us to navigate land and sea, and while there is much about the cosmos that we do not yet know (with increasing knowledge comes an increasing knowledge of our own ignorance), we can be certain that the constellation of Saturn and Venus on your day of birth is not an indicator of your level of extraversion or agreeableness. And yet, astrology is back-still as wrong as ever, but no less feeble-minded.

Mainstream outlets have taken notice. The New York Times regularly dips into the subject, by publishing a profile on the astrologer Chani Nicholas or deliberating on the question " Will Coronavirus Kill Astrology?" (The disappointing answer appears to be: no). A quick Amazon search reveals a proliferation of books that hail astrology as a way towards "radical self-acceptance" or promise to make it fit for the twenty-first century. On Instagram and YouTube, content creators are beginning to babble about their star signs or even devote whole channels to mystic content. Consider the YouTuber Lavendaire, who instructs over five million viewers on how to read their birth charts. But beware, she adds, never publicise your exact date and time of birth, for if people know your full birth chart, they "will know a lot about your fates and people can use it against you."

For all our scientific progress, the prevalence of astrology even among people who do not consider themselves religious serves as a reminder that superstitious and magical thinking is still simmering under the surface. Of course, the latest astrology craze is not authentically novel. Ronald Reagan notoriously consulted his astrologer on decisions like the timing of his re-election announcement and the military invasion of Grenada. The 1970s saw the spiritual awakening of the New Age movement. And even as far back as 1953, Theodor W. Adorno was moved to analyse an astrology column in the Los Angeles Times.

Adorno noted that the modern individual is dependent on a vast web of bureaucracy, which stretches from the state to the allegedly free market, while at the same time being choked by the mass output of the culture industry. Even if people begin to become conscious of their condition, Adorno said, "it is extremely difficult for them to face this dependence unmitigated." Astrology becomes attractive to the individual who no longer believes that she is in charge of her own life and mistress of her own fate.

The German exile drew attention to an apparent paradox: astrology does not liberate anyone from their dependent condition-on the contrary, by accepting that their fates are determined by the movements of celestial bodies believers subject themselves voluntarily to another dependency. And yet, they seek "the aid and comfort given by the merciless stars." Feeling connected to the wider cosmos appears to provide them with a warm spiritual glow.

To an extent, this is perfectly understandable. I find myself in awe when reading about the vastness of the universe, and Stephen Hawking's description of a black hole certainly tests the boundaries of the imagination. But for some, this cosmological reality is apparently too much to bear: believers in astrology prefer their cosmic stories diluted with cheap popular psychology and personality profiles so vague and generalised that a child could see through the trick.

On the other hand, the natural world might not be quite enough for the seekers of astrological comfort. Ever since Copernicus, humanity has dreaded finding that the universe does not revolve around us, that Homo sapiens plays such a minor role in the grand cosmic spectacle. Like religion, which speaks to the individual as if she were perpetually monitored and cared for by a personal God, astrology caters to people's inner narcissists by telling them that the orbits of the planets are not meaningless at all, but really all about them. In the same vein, Adorno observed how the Times columnist's "references to his readers' outstanding qualities and chances seem so silly that it is hard to imagine that anyone will swallow them, but the columnist is well aware of the fact that vanity is nourished by such powerful instinctual sources that he who plays up to it gets away with almost anything."

Unsurprisingly, astrological prescriptions on how to act seem to be rather conformist. "The stars," Adorno wily remarked, "seem to be in complete agreement with the established ways of life and with the habits and institutions circumscribed by our age." This is certainly still true for the more traditional mass media astrological output, but on closer inspection it also applies to the latest generation of spiritual leftists whose astrology is simply conforming to another ideology.

This new generation of astrologers and their followers combine the latest technology of YouTube and Instagram with supernatural beliefs that seem to come straight from the dark ages. Christine Smallwood has pointed out how capitalism has begun to cash in on the trend:

The corporate world has taken note of the public's appetite. Last year, the astrologer Rebecca Gordon partnered with the lingerie brand Agent Provocateur to produce a zodiac-themed event where customers could use their Venus signs to, in Gordon's words, "find their personal styles." This spring, Amazon sent out "shopping horoscopes" to its Prime Insider subscribers. Astrology is also being used to help launch businesses. This summer, the forty-six-year-old siblings Ophira and Tali Edut, known as the AstroTwins, started Astropreneurs Summer Camp, a seven-week Web-based course. Participants analyzed their birth charts to determine whether they were Influencers, Experts, or Mavens/Messengers, and got advice on how to tailor their professional plans accordingly.

All of this seems relatively benign-yet another example of shrewd entrepreneurs ripping off the credulous and superstitious. But Smallwood's story also provides insights into the restless mind of a particularly devout believer:

Ortelee later explained to me that people pop up in the news because the movements of the planets through the sky, known as transits, are activating their charts. This can work on many levels. "When the Titanic happened, there was a big Neptune transit, and when the 'Titanic' movie came out, years later, there was a huge Neptune transit," she said. "You heard Celine Dion everywhere. And now there's a mini Neptune transit, so there's a 'Carpool Karaoke' with Dion and James Corden singing the 'Titanic' song in the fountains in the Bellagio."

Like the whole phenomenon of belief in astrology, this absurd tirade might seem amusing at first, but it reveals a more sinister, psychotic undercurrent to the movement. Assuming that he actually believes what he says, the individual above sounds not like someone who is ironically indulging in a silly fad, but more like a conspiracy nut in need of serious attention. Instead of engaging with reality, he is obsessed with finding patterns and mysterious background forces where none exist.

Many believers in astrology read about their star signs with a wink and try to turn their critical faculties back on again after having gone through a YouTube video about the season of Taurus, or whatever it might be. And yet, the perpetuation of this piffle is more corrosive than it may appear at first sight, especially in an age when the forces of reason are in retreat and paranoid conspiracy theories are on the rise. Is this resurgence of astrology just another symptom of a deeper societal malaise? Perhaps, but this does not mean we have to respect or indulge it. In fact, we'd do better to find the cure.