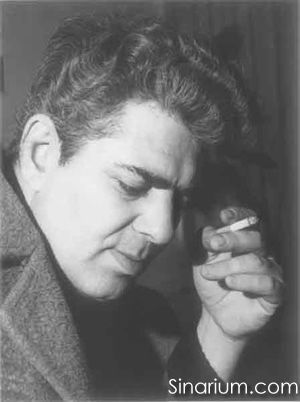

Ahmad Shamlou wrote "The Tablet" (in Persian: «لوح») in 1964, when he was 38 years old. This poem is from the middle stage of Shamlou's life as a poet, when he was already a recognized poet in Iran. The Tablet has political, atheistic, and anti-war themes.

The Tablet is among my most favorite poems by Ahmad Shamlou. I translated it when I was an undergraduate student. A cool teacher at Mazandaran University, Mr. Iman Poortahmasbi, helped me with the editing back then. I got it published in a literary student journal named Derafsh-e Mehr, which I managed at the university. But since then I have changed many parts of The Tablet as my understanding of it changed.

I invite you to read my essay on Ahmad Shamlou if you like. You can also read some more translations of Ahmad Shamlou's poems here on Sinarium. But first, Read The Tablet:

Ahmad Shamlou

Ahmad ShamlouThe Tablet - A Poem by Ahmad Shamlou

As the dark clouds passed,

under the livid shadow of the moon

I saw the square and the street

that looked like an octopus stretching its languid legs to every direction

in a deep gray ditch.

And on the cold pavement

people were standing

in multitudes.

And their long waiting

was turning into

despair and strain.

And each time

restlessness of waiting

that vibrated their collectivity,

was such, as if

there has been a twitch in an animal’s skin

when feeling a cold drop of water

or an itch.

□

Photo by Klaus Kampert

Photo by Klaus KampertI stepped down the dark stairways,

with the dusty tablet

on the palms of my hands.

I stood

on a small landing

which overlooked the square by a half-pike.

And I saw the people

in multitudes,

Who filled the space

all around the square,

as they did the space inside it;

And the rest of them

were on each and every street leading to the square,

and their extension stretched far as to

to the margins of shadows and blackness;

and like a wet ink

spilled out

in the darkness.

And with them there were

waiting and silence.

Thus, I held up

the clay tablet

with the tips of my fingers,

And I cried unto them:

“_Everything that there is

is here

and beyond this

there is nothing

but this.

This is an old

weary tablet,

But here_ lo!

Though it is smudged with

pus and blood

of many wounds,

it speaks of mercy and friendship,

and of innocence.”

The mass but had no

ear or heart for me;

It was such, as if in looking forward

there was a benefit

and a pleasure

for them.

I yelled, that:

“_If you have nothing up your sleeves

with waiting,

then it is vain, what you are doing;

the final message

is but this!”

I cried out:

“_That era when you mourned for your crucified Jesus

is over;

because now

each woman

is a Mary.

And each Mary

has a crucified Jesus,

without a crown of thorn, a cross, or Golgotha;

without a Pilate, the judges, or the jury._

Jesuses with a similar destiny,

Jesuses who all look the same;

with the same garments,

and with the same shoes and putties _all the same as they have been described_

and with an equal share of bread and soup

And if you do not have a crown of thorn to wear,

you have a helmet;

And if you do not have a cross to bear,

you have a rifle.

And each supper

might be “The Last Supper”;

And each look

might be the look of Judas.

But do not wear your feet out

by chasing after

The Garden,

because you will meet the tree

on cross

instead,

when the dreams of mercy and humanity

softly and lightly fades

before your eyes

like a mist,

and the burning bluntness of reality

pierces your eyes

like spars of the desert sun,

and when you perceive how unfortunate_

how unfortunate you are!

and that it would have sufficed if you had much less,

to feel more blissful:

a hail with sincerity

a handshake with warmth

and a smile with honesty.

But you have not been provided with this least of grace!

Nay,

do not wear your feet out

by chasing after

the Garden;

for this is not the time for praying

nor for a curse,

Neither for forgiveness

nor for spite.

And alas that the path of the cross

no more

leads up to the sky

but leads to the inferno

and eternal wandering of the soul.”

□

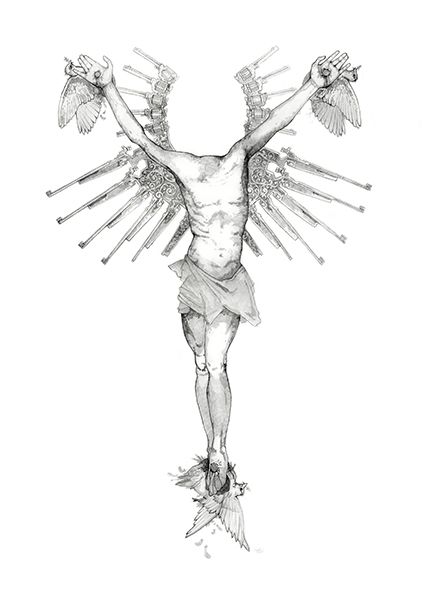

Drawing by Richard Olmsted

Drawing by Richard OlmstedAnd I cried in my heavy fever

and the mass

gave neither heart nor ear to me.

I learned that

these people

did not look forward to

a tablet of clay,

but a book

and a sword

and sentinels who would assail them

with whips and maces,

and would subdue them to kneel,

before the one who

comes down the dark stairs

holding a Book and a Sword.

Thus, much I wept

_and every teardrop of mine was a truth;

though truth

itself

is nothing but a word._

as if

I was repeating

a despairing truth

by such weeping.

Oh,

these people

look for the terrifying truths

only

in the legends;

and that is why they take the sword

as the emblem of eternal justice;

because in our time

sword

is the weapon of the legends.

Also, that is the reason

why they

only

take him as a martyr in the path of truth,

who uses his chest

as an aegis before

a “sword”.

As if they do not prefer

torture, pain, and martyrdom

_which are very ancient things_

to be done with modern tools;

otherwise,

those many lives

that burnt

with the fire of gunpowder!_

otherwise,

those many lives,

of which

only

a vague shadow remains:

a number

among the terrifying figures of thousands and thousands!_

Oh,

these people

look for the truth

only in the legends;

Or

they find the truth

to be nothing

but a legend.

□

Photo by Klaus Kampert

Photo by Klaus KampertAnd my fiery speech did not kindle them

because about the Skies

I said the final word,

without speaking

of the Skies.

Featured images are by Klaus Kampert and Richard Olmsted.

Read the full article