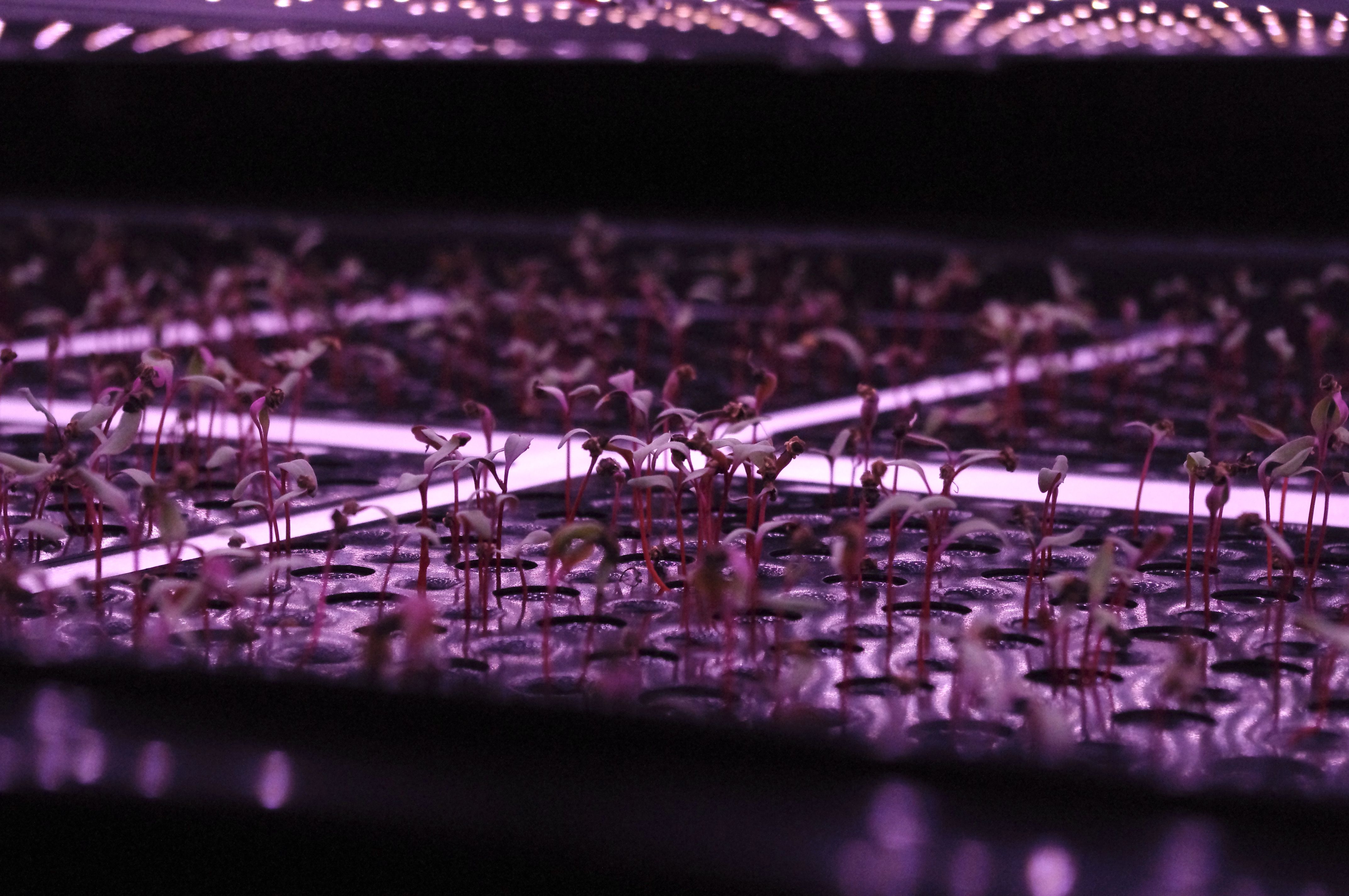

For now, most vertical farms choose to focus on growing leafy greens for several reasons; for one, most of their biomass can be sold – compared to other plants where only the small fruit is edible / Credit: Selina Oberpriller.

On the outskirts of Copenhagen, at Denmark's main fresh food depot, fruits and vegetables are no longer just stored and transshipped; thousands of crops are being cultivated right inside of one of the industrial buildings. Nordic Harvest's warehouse, sprawling over 7,000 square meters, is aiming to become Europe's largest "vertical farm". Here, metallic shelves stretch fourteen stories high into the ceiling above. There is no sunlight or dirt, just hundreds of thousands of LED lights and a water-based nutrient solution on each level to sustain the lettuce, kale, and herb plants.

The leafy greens can be on supermarket shelves by a truck-delivery across the country, rather than shipments from Spain and other warm locales, which are Denmark's primary sources for these vegetables during winter. Nordic Harvest's first harvest was distributed to major supermarket chains Føtex and Bilka across Denmark at the end of April.

In 2019, Allied Market Research predicted a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 24.6% between 2019 and 2026 for the vertical farming market size. While it was valued at $2.23 billion in 2018, it is projected to reach $12.77 billion by 2026 with Europe being the region with the biggest expected growth (CAGR 26.0%). As a reason the study names growing concerns over the availability of water in the Southern parts of Europe. One of the main advantages of vertical farming is its low water demand, Nordic Harvest for example says their farm needs up to 250 times less water compared to the cultivation on a field.

Another point of pride for the Nordic Harvest founders is that the crops are untouched by a farmer, or practically anyone else before the customer unpacks them. "The consumer will be the first one to touch the plant with his bare hands," Anders Riemann, founder and CEO of the company says. The company also claims that its food production requires 250 times less space compared to open field cultivation, no pesticides are used and 100% of the farm's energy comes from windmills. Additionally, the products are supposed to be durable for longer and even to have stronger flavor than vegetables grown in a traditional way.

By definition, vertical farming simply means cultivating plants in multiple levels atop of each other. That makes it a very space-saving growing method and allows food to grow close to where it is consumed, which is mostly in cities. This might become particularly relevant in the future as more and more people come to live in urbanized areas that don't provide space for outdoor agriculture.

"Taiwan for example is trying to strengthen the local production of fresh foods to become more independent of imports,'' says Sabine Wittmann. Wittmann is a vertical farming researcher at Hochschule Weihenstephan-Triesdorf (HSWT) in Germany, who has visited vertical farms in Taiwan and other Asian countries.

However, Nordic Harvest does not focus solely on the supply of the nearby metropolitan area of Copenhagen; it transports its products to supermarkets all across the country. According to Riemann, once at its full capacity his farm will cover one of the 20 tonnes of lettuce, kale and herbs annually consumed by the Danish population. This implies that 20 vertical farms of its kind - each the size of a soccer field - could cover Denmark's full demand for these products of which currently only 30% are produced in the country. Right now, the farm is starting production at 250 tonnes, one fourth of the full capacity.

Even though 61% of Denmark's densely populated land is used for agriculture, the plants typically grown in vertical farms are not the ones requiring a lot of space. Vegetables, potatoes and fruits together account for less than 5% of the space needed to grow all the food a person consumes. And in Denmark, 75% of all crops grown in the country are not even used directly for human but for animal feed.

As many other vertical farms, Nordic Harvest uses a hydroponic system. A nutrient recipe that meets the specific needs of each type of crop is added to the water.

"While the nutrient content in the open land differs from area to area, in the indoor farm we are able to create the ideal conditions for the plant," says researcher Wittmann.

Hydroponics is a circular system, where the water is collected and reused instead of draining away in the ground. Thereby, Nordic Harvest guarantees the only water leaving the farm is that contained in the plants. But hydroponic systems also pose risks. While soil presents natural water storage, this buffer is missing in hydroponics. "The outage of the watering system could cause huge problems, it might even destroy the whole yield," Wittmann says.

As nothing gets lost in the ground, less fertilizer is needed in hydroponic culture than in the open field. Other than many vertical farms which use industrial fertilizer, Nordic Harvest buys plant waste from local farmers that is fermented into biological fertilizer by bacteria in the in-house laboratory. The minerals that the plants need to grow and that occur naturally in the open field must be added to the solution as a powder. These nutrients are obtained in mines all over the world. Riemann says, "instead of degrading a lot of soil like a traditional farmer does, it is better to just destroy an area like a mine."

The 15 of Nordic Harvest's 25 employees who are working directly inside of the farm, are mainly operating machines. The replanting machine that gives the plants more space after the first days of sprouting, the automated guided vehicles, little robots that pick up the trays once the plants are ready to be harvested, the root-cutting machine and finally the weighing and the packaging machine.

However, other steps in the procedure are still done manually, for example an employee has to go through the shelves and adjusts the height of the light boards manually with a spanner, so they don't burn the plants as these grow and once the crops are ready for harvest, colleagues have to take out each tray from the shelves by hand and bring it to the ground by a lift. These steps are supposed to be automated later on, "but first we have to earn some money", Flemming Dyring, Nordic Harvest's CCO, explains. He's dreaming of using a drone for quality control, flying through the shelves, and reporting any error to a computer, so staff members would just have to check these reports instead of all the plants.

Everyone inside of the farm is almost dressed up like the health personnel at a Covid ward. Not only are they wearing face masks - which is nothing extraordinary these days - but their whole body is covered: rubber gloves, a hair net and an overcoat for shoes, pants and top. Before entering, each person needs to sanitize their hands and pass an air lock. A vertical farm is a closed system. As no pesticides are used, everything and everyone entering from outside is a potential risk which could bring in pests.

The indoor farm allows for absolute control of the environment the plants are growing in. This includes full control of the temperature, humidity and light the plants get and ensures complete independence of solar radiation. "We can extend days to up to 20 or 24 hours of light," says Wittmann. A higher amount of light per day stimulates the plant's growth and thereby shortens its cultivation period which improves the farm's profitability.

With 24 degree Celsius, an air humidity of 80% and twelve hours of light a day the climate inside of the Nordic Harvest farm is quite the opposite to the cold and dark Danish winter. Hence, the cultivation is independent of the seasons as well as of extreme weather events such as droughts or floods, which farmers globally have been facing more often in recent years and which will become even more frequent due to climate change.

"While a traditional farmer in Denmark can only cultivate for six months and harvest twice a year, we can cultivate all year and as our cultivation periods are between 22 and 26 days, we can harvest on average 15 times a year," Riemann says. Once their production is in full swing, Nordic Harvest is expecting a daily output of 800 kg per day, harvesting five days a week.

It was three o'clock in the morning when Riemann was in the metro on his way back home from his workplace, a big Danish investment bank, in 2014 and a thought struck him: How far has technology gotten in the development of LED lights? The next morning, the project manager woke up and spent 20 hours researching the effect of LEDs on photosynthesis. His calculations finally showed that photosynthesis could possibly be cheaper with LED diodes than on farmland.

It was a combination of frustrations on a personal and a societal level that motivated him to keep thinking about the issue. Due to his profession he knew that some things are easier to approach at a large scale than on a small scale. And Riemann had the skills to manage big projects. What followed was a year of research at after-work hours and on weekends. To confirm that his thoughts didn't only make sense in his own head he contacted Dr. Dickson Despommier from Columbia University.

Dickson is known as one of the founding fathers of vertical farming. In 1999 the professor and his students came up with the first idea of a skyscraper farm which was supposed to feed the population of New York. In 2010, around the same time the first prototypes of vertical farms were built, he published the book "The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century".

After Dickson had read Riemann's email, he invited him to New York to pitch his idea. Riemann still remembers the sentence Dickson said after the presentation: "You're in the game." This was confirmation enough for him to quit his job at the bank. Through Dickson he got in touch with the YesHealth Group from Taiwan, a pioneer in the vertical farming industry, and with other people to collaborate with.

They spent the following four years developing the technology, looking for potential buildings for the farm and approaching investors. Riemann spent all his personal savings during that time until he managed to close the investment round last year. Fifty individual investors put in 62 Million DKK (8.3 Million EUR or 10 Million USD).

Being profitable is, according to Riemann, the most important factor regarding the types of plants he grows in his vertical farm. Currently Nordic Harvest grows basil, rocket, baby spinach, baby kale and two types of lettuce. Wittmann, the vertical farming expert from Germany, says: "Technically, every plant could be cultivated in an indoor farm. If we wanted to, even a tree." But economically that would not make a lot of sense. Most vertical farms produce leafy greens or sprouts as these meet all the current constraints for vertical cultivation to be profitable. Those crops have short cultivation periods of less than a month. "The more often we can harvest, the higher the profitability because we can generate more crops per time," Wittmann says.

At the current capacity, Riemann is expecting a profit this year of zero for Nordic Harvest. Only after the quadruplication of the production, to its full capacity, expected by the beginning of next year, he's hoping for a profit of about 10%.

But how can a farm with a constant temperature of 24 degree Celsius, 80% air humidity and twelve hours of light a day be sustainable? The think tank Frej is working towards an increasingly sustainable food production in Denmark by creating a dialogue between the different actors of the food industry.

Anna Bak Jäpelt, one of the organization's project managers, does not talk about becoming 'sustainable', but about becoming 'more sustainable', as defining sustainability as a whole is hard. There are three crucial factors: economic, social, and environmental sustainability.

"In many ways vertical farming is less demanding than open field or greenhouse production", she says, "but there is one really big problem, and that's the energy demand. That makes it less economically and environmentally sustainable."

As more than 80% of the Nordic Harvest's energy goes into lighting, the startup has developed its own LEDs, which are supposed to be particularly power saving. This is also one reason for the specific bluish, violet light in the farm. "Blue affects the growth of the leaves, red is important for the seeds and later in developing the flower," CEO Riemann says.

However, this does not mean that the plants at Nordic Harvest grow faster than they naturally would with the full, white spectrum. "The reason why we mostly have the blue spectrum is that we can save energy for all the other spectrums that our plants don't need," he explains.

Despite the inside temperature of 24 degree Celsius the farm doesn't need any heating. Just like in most vertical farms the LED lights extract so much warmth that the farm rather needs to be cooled. As the hall Nordic Harvest is based in was newly built four years ago, it is equipped with central cooling, a technology that sends cold sea water through pipes. So, the only part they need to cool additionally is the storage room, which accounts for 5-10% of their energy usage, Riemann says. The remaining 10% is used for pumps.

All this energy comes from wind power. Nordic Harvest has bought certificates for windmills which produce just as much energy in one year as the farm uses. Once the production has fully started running the LEDs will only be turned on at night - another way to be more efficient. As the demand for electricity is lower at night there is often a surplus of wind energy which leads to negative electricity prices. "Vertical farming fits very well in the expansion of the renewable energy sector," Riemann says.

Bak Jäpelt from Frej sees certificates for windmills critically: "At the moment, claiming that you use renewable energy sources may take the renewable energy from other needs in the society because it all goes on the energy grid and there is a finite amount of energy on there," she says. But if a farm would buy their own windmill and use its energy directly for the production, "that would be an environmentally more sustainable production form."

"Through a plant recipe we decide which taste we want the plant to have, whether it should taste strong or mild, sweet or sour," Nordic Harvest CEO Riemann says. According to Wittmann, the German vertical farming researcher, this is primarily possible due to the absolute control of the nutrients the plants get. "If I for example cause a higher level of salinity in the nutrient solution, a tomato will show a higher Brix value which means it is likely to taste sweeter," she explains. This is already a widespread practice in horticulture, for example in winter when the light intensities are lower.

As the light's intensity can be controlled in the indoor farm, this is another way to affect a plant's flavor. Wittmann explains this with the example of an apple: "The red side is usually the one facing the sun. That's because the plant is reacting to the high intensity of the blue, short-waved light by developing certain substances, just like sun protection." This protection contains flavonoids which influence the taste, are supposed to prevent certain types of diseases, and are therefore used in pharmaceuticals.

By increasing the blue part of the light spectrum, it is possible to increase these substances. However, according to Wittmann there are no general light recipes yet to trigger a certain effect as this differs from plant to plant and sometimes even between cultivars. Nordic Harvest develops their plant recipes by "a lot of trial and error," Riemann says. "You will start learning which parameters to change when you want a certain property of the plant to enhance or a certain property to decrease. But we are still improving them all the time."

In the US, Asia and the Middle East, indoor farming is an area of big investment already, but the European market is still quite small. One reason could be consumer's hesitation here towards such an "unnatural" way of agriculture. While several studies showed that naturalness of food is a crucial argument for consumers, a 2018 online survey found that German consumers are undecided whether they think growing food with artificial light and in a nutrient solution is natural.

Bak Jäpelt from Frej recognizes two extremes of reactions to vertical farming. "There are the people who want the more natural way of production and they think that this is fake food. But then you also have the consumers who want more biodiversity and climate initiatives, and they need areas for that. So, they see vertical farming as a great way of saving areas to combat the climate crisis." She also thinks the "storytelling" of vertical farming works well: "It just looks cool, people love that."

Wittmann says, as far as known today it is possible to cultivate a plant indoors just as in the open land. However, research is currently being conducted about the role of microbiological processes in the soil and in the air. That means how for example bacteria or fungi are influencing the growth of plants. These microorganisms are missing in the nutrient solution of the indoor farm. "We cannot reproduce that part at the moment. So, in this aspect we can also not claim that the quality is exactly the same," she says.

Wittmann has done research trips to several Asian countries where she experienced a higher acceptance of vertical farming among the population than in Europe: "An extreme example is Japan where people regard everything that is grown outdoors as harmful and see closed systems like the indoor farm as safer. In Europe the opposite is the case."

Nordic Harvest has conducted market surveys showing more optimistic results: In October 2020 20% of the respondents knew what vertical farming was and about 70% were willing to buy these kinds of products. In January this year 28% of the respondents knew what it was and 75% were willing to buy the products. "The consumers are aware of the climate change and they got the message that it is actually possible to produce much higher quality, on less land, with longer durability, better taste and higher food safety," Riemann says.

Whether the customers are also willing to pay the higher prices will only show now that Nordic Harvest's products are in the stores. At Føtex, 75 grams Nordic Harvest rocket cost 20 DKK (2.7 EUR or 3.2 USD), one third more than the same amount of organic rocket. Riemann justifies that premium by the longer durability. Because the plants are packaged only 10 minutes after harvest and they don't need to be washed, he's expecting a waste rate of less than 10%, compared to 20 to 30% for products cultivated outdoors.

Nordic Harvest aims to address the same audience as organic products do, "people who want high quality produce, who are tempted to eat vegetarian rather than meat and who want to be sure there are no harmful pesticides entering their bodies," Riemann says. However, food cultivated in vertical farms cannot be labeled as organic in Europe. Even though no pesticides are used in indoor farms, the hydroponic growing practice is not in line with EU standards that require organic food to be grown in soil.

While this used to be a requirement of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's (USDA) organic certification as well, the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) recommended in November 2017 to allow foods cultivated in hydroponics to be labeled as organic. This has just been acknowledged by the US District Court for Northern California in March.

"In fact, there is a big overlap of the advantages of vertical farming and those of organic agriculture: No use of pesticides, very little water usage, no washout of the soil," says researcher Wittmann. She suggests creating an own label combining all the advantages of vertical farming for marketing purposes.

Nordic Harvest is currently working on such a "sustainable" label with the Union for Danish Farmers that they are planning to submit to policymakers. So far, the company has created their own little marketing batches, saying things like "100% fresh", "0% pesticides", "certified wind energy", "ready to use" and "grown on green energy". Additionally, the company got the ISO 22000 certificate, ensuring the safety of food along global supply chains and GLOBAL G.A.P. which certifies good farming practices, to let their consumers know "that we are doing things in a proper and controlled way," Riemann says.

While Nordic Harvest is currently growing six different types of lettuce, herbs, and kale, they are hoping to grow strawberries by next year and blueberries by the year after. "In five to seven years we will be able to grow different kinds of roots, including potatoes," Riemann says. But different types of crops require different climates. And that is where the farm's scale could pose a challenge. The big warehouse is divided into two main halls; creating smaller rooms with different climate conditions might be problematic. And two other factors are crucial for the expansion: "It depends on the development of the LED lights and if the consumers are willing to pay for the better quality," Riemann says.

Vertical farming is often advertised as a solution to the food demands of a constantly growing and more urbanized world population. However, we won't survive only on leafy greens and sprouts. Therefore, the question arises whether it will be possible to also grow staple crops cost-effectively in vertical farms at some point.

These types of crops need a different set of inputs yet to be developed as they for example need more water which causes weight problems in the shelves. "If we manage to adapt the current structures of the indoor farm, minimize the energy usage or use renewable energy more efficiently and become more progressive in terms of automation, I believe it is feasible," Wittmann says. And she sees potential there: "Grain or potatoes work perfectly in aeroponics and as there is no soil the potatoes don't even need to be cleaned when harvested."

However, according to her, that would not make sense in Europe as the staple crop production outdoors is very efficient here. In other parts of the world on the other hand, the climate conditions are more challenging for agriculture. There, growing staple crops in indoor farms might be an option. Wittmann's department already got requests from African countries as well as Iran which are interested in implementing the method.

But in terms of profit the researcher doubts that selling the fresh produce is the best vending option for vertical farming. Instead she suggests addressing niche markets. At her institute research is focusing on plant's raw materials such as essential oils, flavonoids and anthocyanins, substances of content responsible for the plant's color which can be used in pharmaceutics or for food colorant. "With the options we have [in indoor farming] we can increase these specific substances in the plant and sell them as raw materials. That ensures stable output and quality throughout the year, which the industry demands," she explains.

It's hard to tell yet how well the Nordic Harvest products are being received by the customers, a young Føtex employee at one of the chain's stores in Aarhus says. It's been exactly a week that the leafy greens from the vertical farm have been available here when a couple in their early thirties walks through the vegetable section of the shop, looking for rocket. The woman takes a Nordic Harvest rocket package out of the shelf and takes a look at it. It's her first time seeing the new brand but without recognizing the label that says "grown on green energy" she puts it back on the shelf as her partner shows her that the ecological alternative of Føtex's store brand is cheaper. Even though the man has seen Nordic Harvest's advertisement on Facebook before, neither of them realized what the difference to the product they ended up buying was.

Original